|

Books on Video Games

|

Invasion of the Space Invaders

Author: Martin Amis

Publisher: Methuen

Date: November 1982

Pages: 120

ISBN: 0-458-95350-4

Review: derboo

While Video Invaders had some interesting illustrations, it did shine with content rather than flashy imagery. Invasion of the Space Invaders on the other hand was the original coffee table book on video games. With supersized photos of suave teens in front of arcade machines and beautiful colored screenshot reproductions (and some not so beautiful real screenshots), the look and feel of the period is documented here more than anything else.

Martin Amis apparently wrote it at a very young age, and rather than a serious journalistic work, Invasion comes off as a peer-written lifestyle book, full of casual expressions and forced sexual innuendos. ("If Jumpman gets to the top a certain number of times, Jumpman saves the Lady. You have to be over eighteen to see what he does to her next.") At the same time the author is painting himself as a penniless loser who "can't seem to find any girlfriends." Yep, opening with a somewhat awkward foreword by Steven Spielberg the whole book totally seems to buy into the "video games are a dangerous addiction" thing, but all the while being really hypocritic about it. It's all "video games will drive you into child prostitution with your local pastor, who then steals money from your church, and also get your parent's asses evicted. Now go and play those awesome games!"

Sounds familiar, doesn't it? It's the sort of talk you hear from a "reformed" alky, as he braces himself to describe his latest relapse.

The narrative itself is a very personal one, Amis most of the time talks about his own experiences. So half of the text is anecdotes with whole pages of weird tangents, like the philosophy of high score table initials (COQ, FUC, BUM) or analog cheating with analog cheating by messing with the machines with electric cigarette lighters or "battery-run kitchen gizmos." There is a bit of history, but it's basically just "Nolan Bushnell invented video games, but they were boring. Then came Space Invader. The End." The strong bias for Namco's hit and space games in general is found throughout the book. Video ping-pong was a "moronic fad," and his opinion the new cartoonish games like Frogger and Donkey Kong is equally dismissive:

In acquisitive panic, the video moguls decided to go for the banal fantasies of the nursery, the cinema and the grandstand. I venture to suggest that these games will not last. They will not last because they are boring games."

He does kinda like Pac-Man, although he describes its thrills as short-lived, too, likens the yellow protagonist to a lemon rather than a pizza and doesn't go much into the American Pac-Man craze. The game is only really mentioned in the second of three chapters, where individual arcade games are described together with some winning strategies. Among all the famous classics, one also finds some now obscure games no one remembers, like Gorf and Pleiads. With 45 pages, this section is the longest of the book.

Home console games once again get the shaft, as now all the images are merely black&white, and the focus is on how much inferior the games are to the arcade experience. Mr. Amis also had some trouble setting up the whole thing: "Now you plug in the game power cord, monkey with the aerial switch box, and 'tune' your television to an unused channel. Abracadabra! The word Pelmellivision, or whatever, appears on the screen!" They also have to share their space with LCD handhelds and chess computers.

Rather arbitrary appear the two BASIC source codes for the Sharp MZ-80K, especially since once again commercial home computer games are ignored entirely. The final two pages about video game competitions are interesting (and prove that retro game shirts are older than the NES), but are also oddly placed. If you're hunting down a copy of Invasion of the Space Invaders today, you'd probably do it just for the images. The text is not as informative and doesn't hold up too well, but at least it's funny, in a very '80s sense. The language is very colorful, sometimes almost poetic, like in his closing paragraph on Galaxian:

Now, of course, in the bars of Paris (cheap and exotic drinks, pinball, space games—heaven), the Galaxian machines themselves cringe unused in the corners, rejected, gestured at. How far away their proud dawn now seems! They are leaned on and eaten off, like any old Space Invader. People stub out butts on their screens. Everyone is playing PacMan, or Defending. Soon the machines will be shipped off to some seaside arcade, to wait out their days—slapped to pieces by children, their wires fizzing from the damp air, and dreaming of the great day in '79 when they invaded the space of the Space Invaders.

Browse on Amazon.com

|

|

|

Video Kids: Making Sense of Nintendo

Author: Eugene F. Provenzo, Jr.

Publisher: Harvard University Press

Date: October 3rd, 1991

Pages: 198

ISBN-10: 0674937090

ISBN-13: 978-0674937093

Review: John Szczepaniak

Wow, where to begin with Video Kids? Provenzo's book is not the first to examine the topic of how video games affect children, but it's one of the earliest to treat them seriously, as significant cultural creations. Unfortunately it's also so infuriatingly misguided. In fairness Provenzo makes a lot of good points, and some sections which meticulously dissect games (such as Super Mario Bros 2) are genuinely enthralling, but overall the ratio of bullshit to intelligent analysis runs at 10-to-1.

The starting chapter, discussing Nintendo's monopoly in the market, makes some valid criticisms. He points out the deplorable practices of Nintendo like few others would. He then goes on to criticise the company's wish to enter the telecommunications business. It seems reasonable, but by the book's halfway mark one starts to wonder if some of his criticisms aren't just thinly veiled anti-Japanese sentiment, as was popular at the time. He spends time highlighting points put forth by Dan Gutman (at least a third of the book is actually Provenzo referencing someone else), who criticises Pac-Man, Donkey Kong and Space Invaders for being too restrictive. Whereas games like Asteroids, Defender and Robotron allow noteworthy player freedom. Notice how the first group is Japanese versus the second which is American and European, with Provenzo utterly failing to comprehend the allure of games, despite spending a chapter discussing the topic. The less said about his reliance on referencing the nonsensical ramblings of psychoanalytical academics the better—itís all sex and oral sadism according to them.

Unfortunately things gets progressively worse. A lot of analysis is made of what children actually say, which Provenzo quotes directly. Right away it's clear why you shouldn't trust kids, seeing as their warped descriptions of gameplay events are not only incorrect, but are colouring the judgement of the researcher. It's not just the kids, though, but Provenzo himself. There's a dozen or more factual mistakes regarding in-game details. To give one example, he seems to have convinced himself that RoboCop was one of the top 10 NES games by 1990. Was it really? He openly states his source for such information is developers, programmers and retailers, and then he proceeds to reference RoboCop fifteen times in the book, more than any other game according to the Index (though SMB2 is examined more intensely). Is RoboCop—a movie license to begin with—really the defining game for the NES in America?

Perhaps the biggest offence in the early section of the book is the role Provenzo regards video games as having. He states that unlike textbooks or children's books, which must pass library approval boards, videogame content is dictated by the consumer. This is precisely how it should be! The ironic thing is, while this was true of the computer scene in the US which had total freedom, the home console scene, specifically that of Nintendo, was nowhere near as unrestricted as Provenzo likes to believe. Nintendo had strict internal content policies, similar in style to the Hays Code for films, which crippled the content developers could produce. All the supposed sexism, racism, xenophobia and violence which Provenzo claims the games contain, simply don't exist outside of his mind—certainly not to the degree he claims. Throughout the book he also fails to take into account the cultural origin of the games (usually Japan), and the intentions of the original creators. He claims videogames encourage selfish behaviour and solitary play even with two players, conveniently failing to mention the cooperative two-player games that exist in his charts, such as Contra and Bubble Bobble. It's worth pointing out that we now know Bubble Bobbleís creator made it specifically for two-players, so that guys could play with their girlfriends in arcades, thereby encouraging women to take part. Provenzo also criticises games for not featuring scenarios with group co-operation, despite the existence of RPGs with multiple character parties and games like Maniac Mansion.

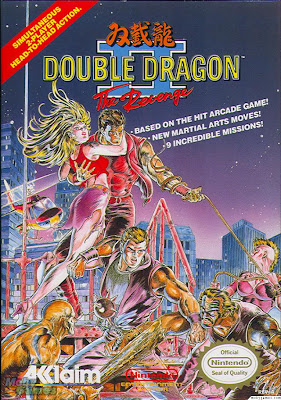

Chapter 5 examines the portrayal of women, and this theme overshadows the entire book. For starters Provenzo is obsessively pre-occupied with gender bias, to the point that all pronouns for third parties become feminised, creating a perverse writing style—ie: "a child is limited only by her imagination." It gets worse when he proceeds painstakingly to build an argument of rampant sexism using sloppy research. He states that game covers are a good representation of a game's content, and proceeds then to judge the degree of sexism in games based on said covers. Which is a fallacy, because covers are often drawn by external artists, and as shown by the Cultural Anxiety website, covers for the US market were often altered from their original versions, which not only changed the intent of the developers, but in some cases they had absolutely nothing to do with the content of the game!

Provenzo goes to great lengths criticising the cover of Double Dragon II (which in fairness uses the same image internationally, only with the remains of Marian's skirt lengthened in the West), because Marian is portrayed as submissive. He also acknowledges the whip wielding woman, commenting on her breast size. Next he draws up a table of 47 game covers, counting the number of males and females, and categorising them into submissive or dominant roles. He says a dominant role is, as one example, someone wielding a weapon. To highlight the endemic faultiness of his research, he then fails to count the whip-wielding woman for the Double Dragon II cover, wrongly counting only a single woman (Marian), and worse still, he fails to acknowledge the whip-wielder as dominant. More mistakes are made with Ultima, Legacy of the Wizard and several others. After the table of 47 games Provenzo proudly proclaims that not a single female was shown in a dominant position, thereby proving that videogames represent a serious threat to the mental health of the nation's children. This, despite the fact that if you follow the criteria he himself sets out, there are several dominant women on the covers listed.

It may seem trivial to dwell on these mistakes with the data, but it's upon these numbers that he fights much of his incorrect arguments. He then criticises games because there aren't ever any women rescuing men - as if this scenario was the norm in other media, and as if videogames are somehow an aberration which defies societal norms. Never once does he acknowledge the fact that since the Greeks started writing their myths millennia ago, heroic men such as Orpheus rescuing women is the accepted traditional scenario. Videogames aren't sexist, they merely reflect thousands of years of human culture.

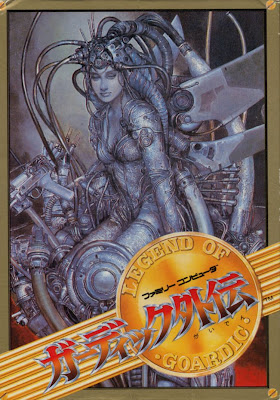

Furthermore, Provenzo entirely ignores games such as Metroid, Phantasy Star and Guardian Legend, to name but three with strong female protagonists. Metroid's omission is forgivable given that Samus isn't revealed until the end, and while Provenzo acknowledges Sega games he states clearly that the book is about the market leader, Nintendo. There's no excuse for Guardian Legend though, given that he mentions it three times in the book, never once commenting positively on its female lead (which is featured on the cover in varying forms for all regions except the US).

For anyone of any intellect, who visits HG101 and has an understanding of game history, it's quite clear that Provenzo has selectively picked and manipulated results, in order to facilitate his own warped agenda. Which is a terrible shame, because as stated there are the occasional nuggets of genuine insight, and he certainly did plenty of legwork when writing the book, even if the research itself was faulty. With 20 years hindsight it's easy to point out the serious flaws and fallacies put forth in Video Kids, some of which could be quite detrimental if taken seriously.

Browse on Amazon.com

|

|

|

Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life

Author: Chris Kohler

Publisher: Brady Games

Date: September 2004

Pages: 312

Review: Kurt Kalata

Written by Wired's Game|Life editor Chris Kohler and published by BradyGames in 2004, the only thing wrong with this book is the title. "How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life" implies a history of how Nintendo saved the US console industry back in the 80s and dominated consoles up until the early 2000s. Rather, it's a series of largely disparate articles about various facets of Japanese gaming, tied together loosely about them all being about (obviously) Japan. There are chapters on MMOs (Final Fantasy XI in particular), rhythm games, game shopping in Tokyo, the video game soundtrack scene, localization, the development of Starfox (mostly interesting due to how it was largely developed by foreigners in conjunction with Nintendo of Japan, a rarity at the time), the roots of Japanese gaming in manga, the attempts to marry narrative with gameplay, and many others. Some sections historical in nature, others are analytical, and yet others are simply interesting collections of trivia.

While indeed there is a substantial amount of topics that are glossed over or simply never addressed - a huge chunk of the book concentrates on Nintendo at the exclusion of Sega, NEC, Sony or other notable companies—when you accept the scope of the book is more limited than the title suggests, it's all quite excellent. Most of the stuff in the invididual chapters could easily be expanded to full books themselves, so some topics may come up short, but as broad level analysis it's all very well done. The writing is lively and although the book is black and white, there are numerous pictures and illustrations to support Kohler's points. There are numerous bits from interviews with Shigeru Miyamoto as well. I've heard other reviews complain about the sections where he lists various Final Fantasy soundtrack albums, but it's just done to illustrate the various styles that its music has been arranged in, and the culture that supports it. Similarly, the section outlining shopping in Akihabara may not be of immediate use to anyone outside of travelers, the description of how pristine Japanese game stores keep their products is sure to rankle the nerves of those familiar with Gamestop's terrible policies.

Of course certain sections are slightly dated - the book was written before the Japanese industry started contracting in the recent HD era, and the chapter on rhythm games predates Guitar Hero and the success of these Western games. Still, a great read, mostly because books that focus on the Japanese side of things, as opposed to the American side, are relatively rare. And it's always great to find a video game book that talks about the games themselves, rather than solely concentrating on their history. Unfortunately, since the book was published by Bradygames, the same group that churns out crappy overpriced strategy guides only to be literally torn up and discarded a few weeks later, the book went in and out of print fairly quickly. Coupled with the high quality of the book, it fetches a higher price on the used book marketplace than most game history books, despite it not being that old.

Browse on Amazon.com

|

|

|

Japanmanship : The ultimate guide to working in videogame development in Japan

Author: James Kay

Publisher: Score Studios LLC

Date: 20 November, 2012

Pages: 248

ISBN-13: 978-4-9906824-0-8

Review: John Szczepaniak

Japanmanship is a hard sell. Its subject matter is genuinely unique, being an English-language guide for non-Japanese game developers wishing to work in Japan, and so therefore it's valuable. Unfortunately its intended target audience is so niche, there can't be more than a few hundred potential buyers at best. Ignoring the focus on games development, how many people do you know in general who are up to the task of moving to Japan, to live and work there?

Not being in that category of reader or potential expatriate, it's impossible to judge the book on its intended purpose. Certainly it seems comprehensive, detailing reasons for making the jump, learning the language, getting a degree and experience, choosing a career path, available jobs, writing a resume (in Japanese), creating a portfolio, interviews, tests and visa applications (in Japanese), types of employment contract, corporate culture (and differences), daily routines, renting a flat, bank accounts, various laws, and much else. This is followed up by a series of reprinted editorials from the Japanmanship blog, interviews with non-Japanese developers living in Japan (at companies like Square-Enix and Grasshopper), and over 250 listings for games companies in Japan with contact details.

Significantly, it's written by an Englishman who made the jump himself, James Kay, who later co-founded the Tokyo-based Score Studios development company. He writes from personal experience, with a perspective ideally suited to the subject matter. In fact the book is an extension of his aforementioned blog, Japanmanship, which detailed his life as a foreigner working in Japan. Many of the editorial essays near the end are taken directly from the blog.

This is one of the strongest aspects of the book, making it appeal to more than just curious job hunters. There's been innumerable essays on the state of the Japanese games industry - everyone who has written anything on video games has probably touched upon the subject, at least twice. Kay however brings a unique insight which only a foreigner working in Japan could have. Given the number of foreigners living in Japan, and the many "books" these same foreigners have written based on their experiences, the majority feel like wasted opportunities, offering nothing new. Japanmanship in contrast will describe an actual scene where Kay was chastised by his Japanese boss, for keeping regular 9-5 hours but working efficiently, compared to a colleague whose work was poor but put in much longer, more impressive hours.

There's a lot of stories about Japanese company life out there, online and in books, but these firsthand accounts are fascinating in their honesty, and because they focus specifically on games development. Significantly, even if you have no intention of working in Japan, reading about everything that happens in a Japanese games company, from the bizarre "bonus schemes" to employee attitudes, it helps re-contextualise what you've previously read about the industry. It provides a new layer of understanding to many of those interviews with developers who seem frustrated or disgruntled. It also explains, using precise mechanical reasons, why Japanese games development lags behind the west. It's less to do with consumer preferences, or "making games more western", which is something we've argued before on HG101, and it's more to do with how companies function.

Having said all that, it's still clear that the book is an extension of the blog, written as a stream of consciousness. Some sentences are difficult to parse, there's a lot of spelling and grammar errors, and in many instances it's more like an informal chat. It's not a deal breaker though, and Kay gets a free pass from us on this, since not only is the book strictly a one-man self-published project, but there really is nothing else like it. Writing books is difficult, requiring tremendous levels of continuous dedication to complete it, and then still finalise and put it out there. If you've not followed his blog before, the reprinting of the essays is a welcome addition. Japanmanship is more than just a job hunting guide, it's a detailed examination of a way of life that exists behind our favourite pastime, and if anything, the biggest complaint is that it's marketed as and focuses more on the former, when in fact the best stuff is the latter.

You can buy Japanmanship on Kindle via Amazon - the UK price is £6.48 ($10.51 in the US). However, if you have the disposable income to buy this version, you might as well shell out a little extra for the Print on Demand version on Lulu. It's nice to feel the pages and make notes on interesting chapters, and it also elevates the company listings in the back to a valuable reference source. Besides, it's the kind of book where it's better to dip in and out of random chapters, than read through consecutively. In our case, the European PoD version cost Ä11.44.

Visit the page at Score Studios for more information.

|

|

|